When to suspect a cerebrospinal fluid leak

Most clinicians are familiar with the features of a post-lumbar puncture headache, with its hallmark severe, global head and neck pain, which is relieved by lying flat.

Less well known is a related presentation that occurs in the absence of a recent spinal procedure — spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid leak.

While uncommon, this condition can result in chronic debilitating neurological symptoms.

Increased clinician awareness has the potential to significantly improve outcomes for this group of patients.

Incidence

Spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak was initially described in 1938 by German neurologist and controversial Nazi scientist Dr Georg Schaltenbrand, and again by Dr Henry Woltman of the US Mayo Clinic in the 1950s.1,2

More recent studies have indicated that this condition has an incidence of five in 100,000.3

The average age of onset is 42 and the condition is twice as common in females.4,5

Anatomy

The brain and spinal cord are sheathed in three meningeal layers: the pia mater, the arachnoid mater and the dura mater.

The subarachnoid space separates the pia mater from the arachnoid mater.

The outer layer, the dura mater, is a tough lining of irregular connective tissue.

CSF is produced by the choroid ventricles, and circulates around the brain and spinal cord in the subarachnoid space.

About 500mL of CSF is produced per day, but with constant production and reabsorption, the normal volume of CSF is 125-150mL.6,7

The CSF provides buoyancy for the 1.5kg human brain.

Cushioned in fluid, the brain has a net weight equivalent to 25-50g.8

Without this neutral buoyancy, the brain can ‘sag’ within the skull causing traction on the pain sensitive meninges, cranial nerves and cerebral veins.

This can cause descent of the cerebellar tonsils.9

Occasionally the bridging veins can be torn, resulting in unilateral or, more commonly, bilateral frontoparietal subdural haemorrhages.

CSF also plays a role in brain cell homeostasis, removal of waste products and acts as a shock absorber for head trauma.8

Pathogenesis

The causes of spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid leak continue to be studied, as more cases are identified with improving imaging techniques.

The following associations have been demonstrated (listed in order of incidence):

1. Developmental nerve root sleeve abnormality

Patients with defects in the dural sheath covering the spinal nerve root outlets, such as a patulous nerve sleeve cyst or meningeal diverticulum, are at higher risk of spontaneous CSF leak.10

2. Degenerative disc disease

This can result in the formation of a bone spur or jagged edge that can pierce the dura and trigger a spontaneous CSF leak.

Treatment in such cases is repair of the dural defect and correction of the spur.10

3. CSF — venous fistula

Little is known about these lesions other than that their incidence has increased as imaging studies have become more refined.

These fistulas result in CSF flowing slowly into the venous system.

4. Connective tissue disorders

Fifty per cent of paediatric cases of spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid leak are associated with a connective tissue disorder, such as Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome or autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease.10

In adults with the condition, 20% have findings suggestive of Marfan syndrome (such as increased height, pectus excavatum, joint hypermobility and high palate) without any other diagnostic features.

Spontaneous CSF leak tends to run in families with a history of aortic aneurysms and joint hypermobility.10

It is thought that these patients could have impaired collagen function, resulting in reduced dural compliance.

Reduced dural compliance by itself can cause orthostatic headaches in these patients even in the absence of CSF leak.

While not common, this is a difficult cohort to treat.

Presentation and clinical findings

Symptom onset can be sudden and severe, with many patients presenting initially to the emergency department.11

The differential diagnosis on presentation includes subarachnoid haemorrhage and meningitis, but the clue on history is the relatively rapid improvement in the headache when lying flat and worsening within minutes of standing.

Valsalva manoeuvre may also worsen the headache.

Around 50% of patients experience neck pain, stiffness, nausea and vomiting.12

They may also report dizziness, vertigo, facial numbness and weakness, impaired vision or a metallic taste.13

These symptoms can arise as an effect of ‘brain sag’ on the vestibulocochlear, facial, optic and glossopharyngeal cranial nerves.10

Over time, the headache can become chronic and disabling.13

Patients with slow leaks may be headache-free after lying flat overnight, only to develop a ‘second-half-of-the-day’ headache.14

In some, the orthostatic nature of the headache decreases with time.

For patients with chronic headaches, it is worth taking some time to determine whether lying or standing affected the headache in its early history.15

Diagnosis and imaging

Diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion.

Ninety-four per cent of patients with spontaneous CSF leak were initially misdiagnosed, with an average time to diagnosis of 13 months, according to one study into the condition published in 2003.16

If a leak is suspected, referral to a specialist with expertise in this area is recommended.

This may be a neurologist (particularly those with an interest in headaches), neurosurgeon or neuroradiologist.

Many patients will undergo a CT brain early in their presentation that may be reported as normal.

An MRI brain with gadolinium and MRI spine with 3D myelogram may demonstrate suggestive features of the condition.

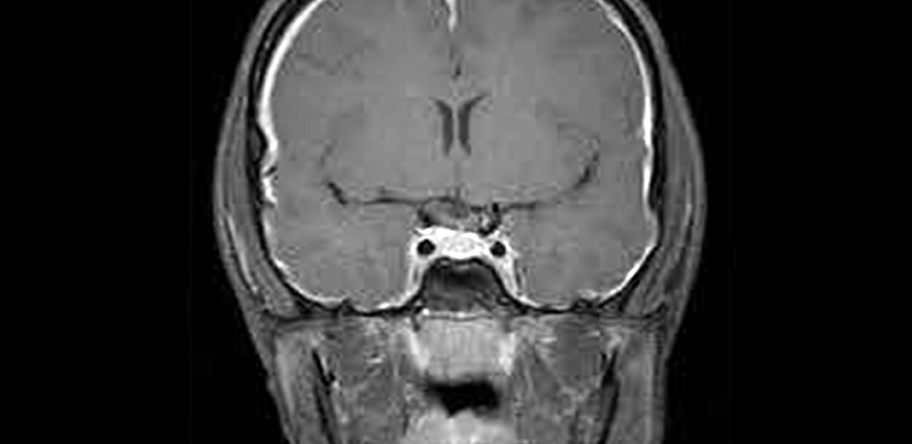

These include pachymeningeal enhancement (when the dura mater looks thick and inflamed), sagging of the brain, pituitary enlargement, subdural collections of CSF and engorgement of cerebral venous sinuses (see figure 1).12

However, MRI is reported as normal in up to 20% of patients.12

Subsequent investigation will depend on operator preference and the available imaging equipment.

Depending on clinical history and initial MRI results, a patient may be referred for lumbar puncture with opening pressures plus a CT myelogram, digital subtraction myelogram with a delayed CT myelogram, or diagnostic large volume patching without further imaging.

Lumbar puncture may demonstrate low, very low or negative CSF pressure, but up to 46% of patients have normal pressures.10

CSF analysis may demonstrate increased protein, increased lymphocytes and xanthochromia.10

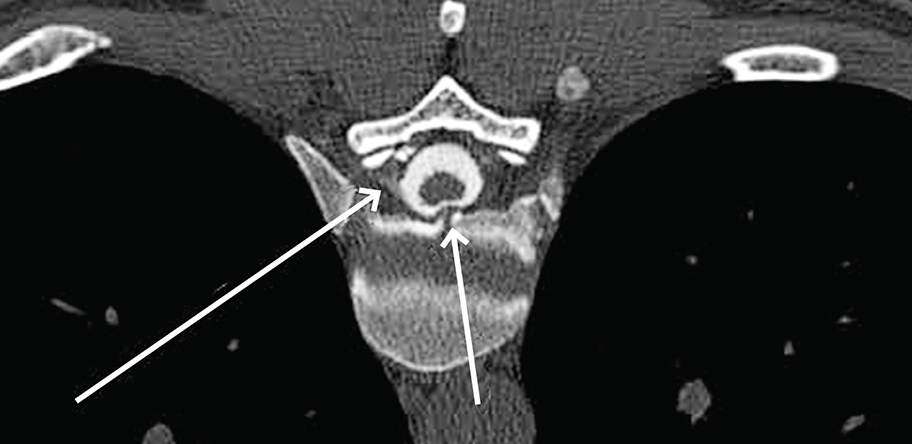

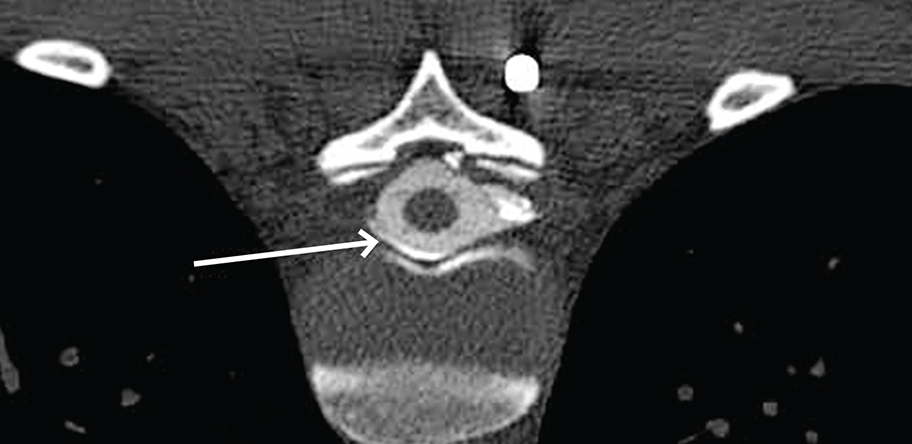

CT myelogram can be used to define the site of a CSF leak.

During this procedure, a lumbar puncture is performed, CSF pressure is noted, and radio-contrast dye is injected into the subarachnoid space.

Any contrast seen outside the dural sac confirms the diagnosis and the location of the leak (see figures 2 and 3).10

A digital subtraction myelogram is performed under fluoroscopy and allows the digital subtraction of a pre-contrast image to enhance the view of the injected contrast.

This method offers advantages in the identification of rapid leaks, leaks ventral to the spinal cord and spinal CSF (venous fistulas).17

Treatment

Some patients respond to conservative measures including bed rest, hydration and caffeine.12

However, many patients require patching or repair at the site of the leak.

Initially this typically involves trial of an epidural blood patch.

This involves epidural injection of autologous blood at the level of the leak, usually performed by a neuroradiologist.

The clotting factors in the autologous sample track circumferentially in the epidural space and repair the defect.

Epidural patches may need to be repeated with different volumes of blood, but are effective in 60–75% of cases.8,10

Fibrin glue may be used instead of blood in targeted patching at a confirmed leak site, and is a more stable and longer lasting treatment option.10

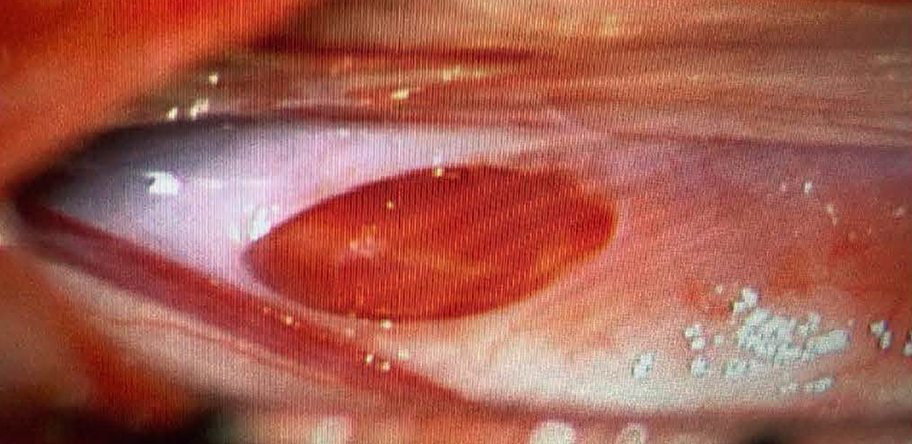

Patients who do not respond to patching require neurosurgical review (see figure 4).

Surgical approaches to dural defects include suturing, ligation and clipping.

Alternatively, application of a small compress sealed with gel foam and fibrin glue may be effective.10

Conclusion

Spontaneous CSF leak is an uncommon but potentially highly debilitating cause of headaches.

Given that a number of effective therapies are available, it is important for clinicians to consider this diagnosis, particularly when there is a history of orthostatic headache.

Dr Ruth Myers is a GP with a special interest in aged care, who practises on the South Coast, NSW.

Dr Scott Davies is a diagnostic neuroradiologist and consultant at the Neurological Intervention and Imaging Service of WA at Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital, Perth, WA.

Acknowledgement: Dr Myers would like to acknowledge her friend Rebecca Somboli, whose experience was the catalyst for this article. Rebecca had undiagnosed CSF leak for 10 years, and following appropriate diagnosis, has now been successfully treated.