An approach to functional disorders

Need to know:

- Functional symptoms are common and can be distressing and debilitating.

- While there is sparse literature on how to approach patients with functional symptoms, evidence-based approaches are helpful to avoid invalidation of symptoms and patient alienation.

- Good communication is a cornerstone, providing a clear and timely positive diagnosis.

- Normalising the phenomenon but recognising the varied severity can help patients accept a functional diagnosis.

- Frameworks that explain the symptoms in an accessible, physiologically based fashion — such as the body stress system approach — may aid understanding and engagement.

- Tailor assessment and management to the individual, including patient preference for strategies that encourage healing and sustain the restorative and maintenance response.

Everyone experiences functional symptoms — be it a twinge, tic, twitch or tickle. These occur frequently and are largely ignored.

Occasionally, however, functional symptoms are more persistent, or debilitating, and may be characterised as a functional disorder: a group of recognisable medical presentations resulting not from disease affecting a body structure but from a change in the function of bodily or organ systems.

Examples may include a cough that will not settle or, more alarmingly, chest pain that may precipitate an emergency admission.

Some are syndromal, such as fibromyalgia or irritable bowel syndrome. And some functional disorders can become severe, with multiple disabling and distressing symptoms that are not amenable to any standard medical treatment. These may be at play for a number of our heartsink patients.

This article outlines an approach to normalising the phenomenon of functional symptoms with patients. It provides a simple model based on physiology to explain symptoms and to aid diagnosis and treatment.

A functional framework

Experienced GPs tend to develop their own ways to approach and manage these patients as there are few guidelines. And yet, there are expert centres around the world that are developing effective practices.

This article is based on one such framework, the body stress system approach, developed by Dr Kasia Kozlowska, a child and adolescent psychiatrist and clinician researcher with an interest in functional neurological disorders at The Children’s Hospital at Westmead and Westmead Institute of Medical Research, University of Sydney.1

In the general practice setting, the three categories outlined in box 1 can help the clinician construct a management plan. It is worth considering additional treatment options for each subsequent category.2

| Box 1. Categorising functional presentations |

| 1. Persistent functional symptoms: Ongoing non-specific symptoms that are burdensome enough for the patient to consult a doctor but are not classified as disease. Nausea, cough, itch and headache are some common examples. 2. Functional somatic syndromes: Syndromal disorders, such as fibromyalgia or irritable bowel syndrome, are better described and have agreed management guidelines. Other examples include migraine, persistent fatigue and complex regional pain syndrome. 3. Somatic stress disorders: Complex chronic conditions with multiple symptoms affecting several body systems but not falling into a clear syndromal category — often with associated mood change. These patients have unique stories, which may vary over time. Investigations fail to elucidate the diagnosis. Frequent hospital admissions and multiple healthcare providers add to the confusion. These disorders can be superimposed on known medical conditions. |

Communication is key

The functional patient needs to know:

- Their symptoms are real and are taken seriously.

- That appropriate tests will be done to ensure organic disease is excluded.

- That functional symptoms are common and troublesome but not dangerous.

It is important to avoid colluding with the patient’s anxiety and fear of organic disease. With this in mind, investigation should be limited to those that are appropriate for the clinical presentation. Repeated testing is not recommended unless clinically indicated.

Once satisfactory investigations have been performed to exclude organic disease, give a clear diagnosis: “It is reassuring that all your investigations are normal. You have what is called a functional condition. Now we can focus on the best ways to manage your symptoms.”

It is important to explain the phenomenon of functional conditions clearly and in terms that the patient can accept. A useful metaphor is a computer: physical disease is like a hardware problem, whereas functional conditions resemble software issues. The challenge of management is how to approach reprogramming.

Phrases like ‘there is nothing wrong with you’ or ‘it is in your head’ are inaccurate and unhelpful. The term ‘psychosomatic often fails to explain symptoms: the racing heart and muscle tension that follow a painful stimulus are not psychosomatic, but they are functional.

Is it helpful to call nausea that is experienced when smelling something foul psychosomatic? Additionally, people with low health literacy can be upset by the term ‘psycho’. It is best avoided.

The patient who wakes with chest pain or with sudden paralysis that came out of nowhere will understandably feel invalidated by the insinuation that their symptom is psychological. And yet, when appropriately investigated, there is no physical explanation.

This is where the body stress system framework may be helpful to explain functional conditions.

Explaining the symptoms — the body stress systems

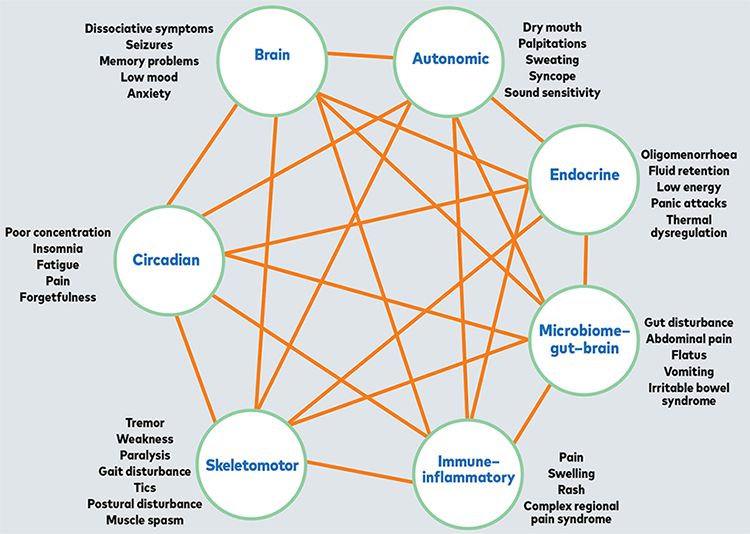

There are seven body stress systems in the framework — namely, the brain, circadian, autonomic nervous, endocrine (including the hypothalamic–pituitary axis), skeletomotor, immune–inflammatory and microbiome–gut–brain systems.

Diagrams can be a useful tool to help explain the systems, as well as the impact of contributing factors on their manifestation (see figures 1 and 2).

Box 2 outlines an approach to explaining each system.

| Box 2. Explaining the systems |

| The circadian system: This is a good place to start because most patients with functional symptoms have some deterioration in sleep quality. Many will be painfully aware that good-quality sleep is essential for health. Every cell in the body relies on a functioning circadian system for maintenance and restoration. The brain system: Explain how the brain co-ordinates all responses and is the source of activation of most other systems. There may or may not be awareness of stress responses. The autonomic nervous system: Point out this is highly reactive second by second. It can be helpful to list the physical responses that occur with sympathetic activation. The endocrine system: Hormonal systems are affected by the stress response. It may help to outline how the patient’s primary symptom/s may be affected by hormones. For example, antidiuretic hormone affects fluid retention, and cortisol levels influence energy. The hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis is activated through subconscious hormonal activity. The skeletomotor system: Activation through primitive reflex responses may lead to muscle tension, pain, twitching, tremor, weakness or paralysis. The immune-inflammatory system: This is only partly understood but may be the cause of rashes, swelling, pruritus and, most importantly, pain associated with stressors. The microbiome–gut–brain system: This is extremely complex and incompletely understood. Many patients accept that both diet and stress can disrupt gut function. This system is commonly affected in children. |

These highly interactive systems are responsible for much of the body’s function and are not under conscious control. Explain how they operate in two modes: restorative and maintenance mode, and defensive mode.

The restorative and maintenance mode may also be known as ‘rest and digest’ or ‘feed and breed’ mode. Good vagal tone (good activity of the vagal nerve and higher capacity to deal with stressors) is a concept that has been popularised on social media so may be familiar to some patients.

It is important to emphasise that human health requires that we remain, for much of the day, in the restorative and maintenance mode, when repair and rejuvenation occur.

The defensive mode is activated when the body perceives a threat, real or imagined. Along with the ‘fight, flight or freeze’ responses, the body stress systems are triggered, which can lead to unwanted changes.

Functional symptoms will arise if the defensive mode is activated for prolonged periods or is severely triggered with excessive sympathetic activation.

In this manner, all functional symptoms can be explained by identifying which body stress systems have been predominantly activated. For example, the endocrine system has been affected in the patient with hypothalamic amenorrhoea, or activation of the immune–inflammatory system can lead to rashes and pain.

Standard clinical approaches and systems methods often fail to identify the causes that lead to the defensive mode being triggered. However, GPs know the psycho-biosociosexual background of their long-term patients, which places them in an excellent position to help identify the broad range of potential triggers to the body stress systems.

Four questions that can help illuminate the contributing factors are outlined in box 3.3

It may help to use diagrams, such as those shown in figures 1 and 2, to both illustrate the pathogenesis and seek background causes, which may not have been mentioned.

| Box 3. Illuminating the triggers |

| – What was going on in your life around the time your symptoms first arose? – How did you feel about what was happening? How did you respond? – What about the situation troubles you most? What did it bring up for you? – How are you handling that? Did you seek further information and advice from friends or Google? |

Management

Management will be covered in more detail in a subsequent Therapy Update, but a simple summary of an approach to treating functional conditions follows.

Step 1: Give a clear diagnosis

Functional conditions should be treated like any other disorder: provide a clear positive diagnosis followed by the encouraging statement that, with the right treatment, it is manageable.

It is important not to presume psychogenic factors are at play. For example, only one in five patients with functional neurological disorder believe (a priori) that stress has anything to do with it.4 Making assumptions about the role of stress implies that the patient has contributed to their condition or is somehow responsible. This is shaming and alienating and will harm the therapeutic relationship.

Try to avoid negatives, such as, “Your tests show nothing wrong,” or ‘We cannot find a medical explanation for your symptoms.” A functional diagnosis is a medical diagnosis. Functional neurological disorder is listed in DSM-5, and a number of functional conditions are listed in the ICD-11. How this diagnosis is given is critical to recovery.

Step 2: Use the body stress system model

This approach can help to shift the diagnostic paradigm.

Step 3: Clarify which body stress systems have been activated

Talk through any questions with the patient to ensure you have a shared understanding, and then draw up a management plan that is suited to the patient’s situation, using the factors listed in figure 2.

A common feature of functional symptoms is they tend to worsen when attention is given to them. One of the clinical challenges is to help the patient to focus instead on re-establishing a sustained restorative and maintenance mode.

Outline that this is a key management goal. The means to achieve this should incorporate the patient’s preferred method or methods that can be accessed readily and used preferably on a daily basis to reduce the body stress response.

Step 4: Build a team to enable healing

It should be evident that functional conditions are highly individual and arise as a result of a unique congregation of factors. Similarly, not only is treatment individualised but a strongly patient-centred approach to recovery is also needed.

The less psychologically minded may do better with physical therapies, such as yoga/tai chi/qi gong or simply time in nature.

If your patient has a relationship with any therapist practising a modality that can reduce sympathetic activation, encourage a course of therapy and review.

Engaging a psychologist, physiotherapist, occupational therapist, massage therapist, exercise physiologist or counsellor who can work with the patient to achieve balance is a helpful adjunct.

Many people are using wearable devices to track sleep, heart rate and, especially useful, heart rate variability. It may help them to observe symptomatology in response to their interventions.

While remaining in the workforce may be beneficial, patients need to consider adopting a lifestyle that prioritises the restorative mode.

Step 5: Arrange timely review

Agree to review symptoms as often as is necessary to assure the patient of ongoing support while they focus on the best way to achieve the agreed goal.

Conclusion

The diagnosis and treatment of functional conditions may require a radical shift in approach by both doctor and patient alike.

The focus of this Therapy Update has been communication of the diagnosis and a general management approach to patients. A subsequent article will outline the top-down and bottom-up approaches to management.

Read Part 2: Functional disorders — top-down or bottom-up?

Dr Gillian Deakin is a GP in Bondi, NSW. She is also the author of 101 Things Your GP Would Tell You If Only There Was Time, and her second book What the hell is wrong with me? A guide to treating fatigue, pain and other unexplained symptoms is due for release in July 2024.