Who are the 29 GPs recognised in the King’s Birthday Honours?

A significant number of GPs have been honoured for their contributions to medicine and society in the King’s Birthday Honours today.

This includes Professor Michael Kidd, the former RACGP president who helped save the college from collapse 20 years ago and Dr Rosanna Capolingua, the high-profile WA GP and former AMA president.

Special mention also goes to AusDoc columnist Professor Simon Willcock who was recognised for his contributions to medicine.

The full list of GPs is below. Here we profile some of the winners who once again show the difference GPs make.

We start with Dr Diana Coote and her husband Dr Clement Gordon.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to include a 29th GP. Commodore Nicole Curtis, a GP and medical administrator, received an AM for exceptional service to the Australian Defence Force in operational health, policy and capability.

Dr Diana Coote OAM and Dr Clement Gordon OAM, Warialda, NSW

“Holy cow, Clem, listen to this!”

This was Dr Diana Coote’s reaction to learning she and her husband had both been honoured with OAMs.

Known to their patients Dr Di and Dr Clem, they have worked together in the NSW town of Warialda, 200km northwest of Armidale, since their arrival in 1989.

“We’ve been on call for all those years, we run the hospital, we run the nursing home, we run the general practice,” says Dr Gordon.

“We’re both very proud that somebody in the town has nominated us,” says Dr Coote.

Warialda has no other GPs, which means any medical event in the area is in their hands.

“We had a tension pneumothorax this year,” Dr Gordon recalls.

“We had to put in a chest drain for somebody who was literally dying before our eyes.”

“But we didn’t have the equipment at the hospital, so we made do,” says Dr Coote.

“So Clem used his finger and a glove — and it worked.”

Dr Coote adds that the couple are ideal colleagues because “I do the smears and tears, and mental health, whereas Clem likes the emergency stuff, the orthopaedic stuff, the surgical stuff”.

They met at the University of Queensland, both graduating in 1978, and worked in rural practices and hospitals across the state for nearly a decade.

They finally settled in Warialda, just over the NSW border, with their four children.

Their daughter now works part-time at the practice, alongside a “very good registrar”, caring for around 6000 patients.

“We’re both past retirement age now, but if we left, there wouldn’t be a doctor in Warialda or in the district,” Dr Gordon says.

“As long as we both enjoy good health, we feel like we’ve got a moral obligation to stay and work.”

Both Dr Coote and Dr Gordon were awarded OAMs for their service to medicine.

Professor Danielle Mazza AM, Melbourne, Victoria

“It’s been a recurring theme of my career — senior doctors pointing their fingers at me and saying, ‘It’s always girls like you trying to rock the boat’.”

Professor Danielle Mazza’s contributions have been recognised, particularly her contribution to women’s health, where her advocacy for reproductive healthcare access has made a mark on general practice and wider Australia.

She was inspired by her time working with high-profile UK obstetrician Dr Wendy Savage in the East End of London, treating a “very vibrant population of women, who were very socioeconomically disadvantaged”.

Another formative experience was during her GP training in rural Victoria.

“There was a patient, a woman who had postmenopausal bleeding, who saw another GP who did not examine her, just told her she needed hormone treatment,” she recalls.

“The bleeding did not stop, so she came to see me. When I examined her, she had a large, fungating cervical cancer.

“She died within six months.

“But her husband, a truck driver, has now been my patient for the last 20 years, because we went through this tragedy together.

“And it showed me how women’s health can be stigmatised, how much ignorance is out there.

“That motivated me to improve education and research so we can help more people, and not have these situations.”

Professor Mazza has since authored 200 studies and the Women’s Health in General Practice textbook. She has led the Monash University department of general practice since 2011.

She has also directed SPHERE, the Centre of Research Excellence in Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health in Primary Care, since 2019.

She says the biggest change she has witnessed in women’s health is the status of abortion, which has been fully decriminalised in every state and territory, starting in WA in 1998 and finally in SA in 2022.

But Australia is still behind many other countries, such as the UK and Ireland, when it comes to dismantling barriers to abortion access, she says.

“As we’ve seen in the US, this is a fight that never goes away.”

Professor Mazza received an AM today for significant services to medicine and medical research.

Professor Michael Kidd AO, Sydney, NSW

Professor Michael Kidd is known to GPs as a former RACGP president, and to basically all Australians as the Deputy Chief Medical Officer who played a pivotal role guiding the nation through the COVID-19 pandemic.

But when asked for the experiences that stick with him, his mind goes to the AIDS epidemic in the late 1980s.

“I had finished my GP training, and like all new GPs do, I looked around to decide where I was going to make my contributions,” he says.

“As a gay man, I decided I wanted to contribute by working as a GP with the Gay Men’s Health Centre and the Victorian AIDS Council.”

“Several of my friends had contracted HIV and lost their lives.

“I could also see the discrimination against people with HIV, including discrimination in the health system.

“I treated a significant number of people with HIV, then got to see one of the great miracles of modern medicine — the introduction of effective triple therapy in 1995.

“That was an extraordinary moment to live through as a clinician.”

Among a long list of roles, Professor Kidd has been a senior academic at Flinders University and the Australian National University and led the World Organization of Family Doctors between 2013 and 2016.

He also led the RACGP between 2002 and 2006, steering the college through a financial crisis that was arguably its lowest ebb.

He says the risk the RACGP could have gone insolvent was real and significant.

“But thanks to the RACGP members and staff, we were able to turn around the college’s fortunes.

“I believe the reason people were so behind saving the college was because they recognised how important it was to the nation to have a strong RACGP.”

Professor Kidd continued to volunteer for the front lines of a crisis when the COVID-19 pandemic began, taking the role of Deputy Chief Medical Officer.

He clearly knew the pressure, scrutiny and sleepless nights the role entailed, so did he have any second thoughts about taking it?

“Not at all.

“It’s been an extraordinary privilege to be in a role like this at such a time in our nation’s history.

“It was important to me that the voice of general practice was heard, that primary and public health were entwined effectively and the manifold contributions of GPs and other primary care providers were acknowledged and respected.”

He points out that every GP on the King’s Birthday Honours list “has made a difference to the health and wellbeing of the nation”.

“It is a real honour to be included in such a group.”

Professor Kidd was honoured with an AO for distinguished service to medical administration, to community health, to primary care leadership and to tertiary education.

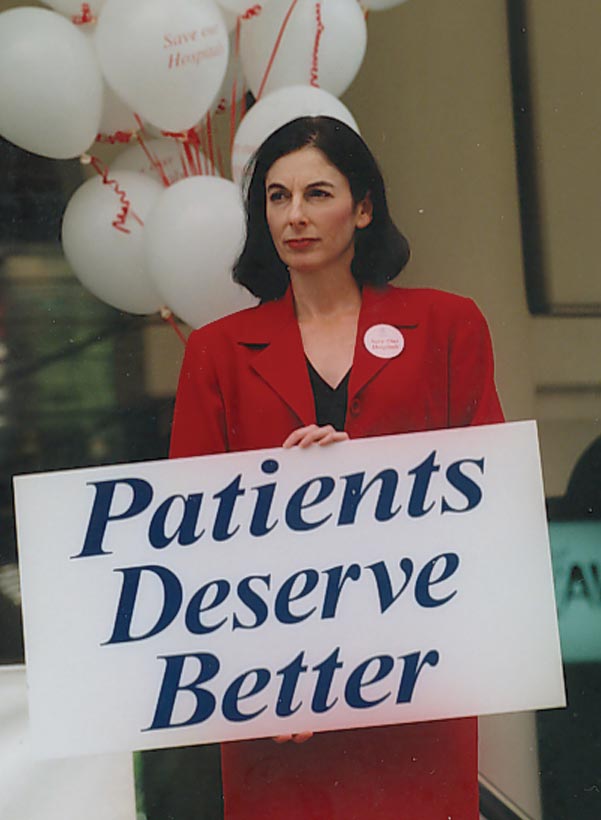

Associate Professor Rosanna Capolingua AM, Perth, WA

Since deciding at age five that she wanted to be a doctor, Associate Professor Rosanna Capolingua says she has never had any regrets — the only thing she would do differently would be to take more holidays.

The daughter of Italian migrants who attended a small school, Professor Capolingua has thrived on a challenge.

It included having her first daughter during her final year of medical school.

“I made it harder on myself but I have no regrets,” she tells AusDoc, adding with maternal pride that her firstborn is now an emergency medicine consultant with three sons of her own.

Her other two children have also followed her into medicine.

In terms of her career, Professor Capolingua says the greatest source of happiness has not been the honours or the high-profile positions or the fact she has become a role model for many women in medicine; it’s been her unswerving focus on her patients and patient outcomes.

“What I’ve always been about is advocacy for them — their access to high-quality care,” she says.

During her time as president of the AMA, her relationship with the then-federal Minister for Health and Ageing Nicola Roxon was the subject of much media interest. It was usually described as “combative”.

Both strong women, they took opposing sides on various issues. But the flashpoint was a controversial speech by Ms Roxon to the Labor Party faithful in 2008 declaring an end to the “historical anomaly” of doctor-dominated healthcare.

In response, Dr Capolingua had many words to say about what was at risk.

Over a decade-and-a-half later, she says there are no bad feelings between the two.

“Nicola faced the challenges of a newly elected ALP government coming to power after years in the political wilderness.”

“She had her job to do, and I had my job to do, but we respected each other,” she says.

“I remember her showing me her wedding photos when she got married while health minister.

“And I never thought we had a terrible relationship at all — I only have fond memories of that time. I certainly don’t have any negative feelings about Nicola.”

Despite the pressures facing the specialty, Professor Capolingua says her passion for general practice remains undimmed.

“It is a great honour that people choose to see you as a GP and that they share not just their physical needs but their personal and psychological needs. It’s such a humbling place to be.”

The big change, the one she welcomes and has fought for, is GPs freeing themselves from Medicare and moving away from bulk-billing to charge fees that reflect the care they provide.

“In my practice we have fees that we advertise to our patients so they know what they might be billed, but we are often discounting our fee or bulk-billing, being sensitive to the needs of the patient,” she says.

“I don’t think my practice is unique; we all feel a sense of community responsibility and that explains why we are not a lucrative part of medicine.”

Professor Capolingua was awarded an AM for her significant service to patient care and being a role model for women in the King’s Birthday Honour’s today.

Professor Simon Willcock AM, Sydney, NSW

Professor Simon Willcock has had 40 years to ruminate about whether he was correct to make general practice his ‘forever’ career as a newly minted hospital-based medical graduate.

And the answer, during all the good times and bad, even during the pandemic and those years when official Federal Government policy was to deliberately defund the care offered by the specialty, has always been that he has no regrets.

“My career has taken me from rural practice in Inverell to Brooklyn on the wilder fringes of Sydney and more recently Marsfield. I still see patients and friends from all these places, noting that as the years go by the friend and patient roles tends to coalesce.

“That has been one of my many joys.”

He talks about having witnessed the “abundance of altruism” given by those generations of medical students and doctors he has supervised, mentored and inspired.

But with that passion comes the pain of seeing what the heavy demands of the work can also do.

“In 2023 I find myself working harder than ever before and witnessing an existential threat to general practice. The burnout is real.

“Many of my older colleagues are deciding to exit clinical practice earlier than they intended, exhausted by the workload and lack of support.

“Younger GPs, many of whom I taught as undergraduates and registrars, and to whom I extolled the wonders of general practice, are asking themselves if they have the stamina to achieve the outcomes they demand of themselves.”

He refers to the myth of Sisyphus and the feeling among younger doctors that they spend all day pushing the boulder uphill only to be made to repeat the task the following morning.

Asked about the biggest changes to general practice over the last 40 years, Professor Willcock, head of primary and generalist care at Macquarie University in Sydney, says it is the integration of technology, including the computer on his consultation desk.

But his enthusiasm is tempered.

“The paradox of technology is that it has both increased my workload and decreased the time available to get that work done.

“Traditional consultation-based models of practice, funded through Medicare or by the patients themselves are not sustainable, and are the primary contributor to the burnout experienced by my colleagues.

“But I do believe that general practice has a future. Absolutely. We all know that when done well it is the pinnacle of good holistic healthcare. It changes lives.”

He says his faith for the future of the specialty lies with the new generations.

“Ultimately, they will come up with the design for change that the over-engineered but vision-constrained government working parties have not been able to achieve.

“The community needs great GPs.”

Professor Willcock was today awarded an AM for significant service to primary healthcare and tertiary education.

Associate Professor Magdalena Simonis AM, Melbourne, Victoria

“I was absolutely overwhelmed and filled with disbelief when I found out. I had to phone the Governor-General’s office to confirm it was real, not a hoax.”

Associate Professor Magdalena Simonis says she now feels humbled having had the “good fortune to acquire the education I’ve had, to study the course I chose, practice what I love and feel like every day counts”.

She says the happiest moment of her professional career was getting into medicine at the University of Melbourne, a dream she had harbored since she was seven.

A GP in Melbourne with a special interest in women’s health, she is now back at the university as honorary clinical associate professor in its Department of General Practice.

She is also a well-known writer.

Back in 2020, the RACGP published her article on the secret history of women in medicine and the life of Dr Constance Stone, Australia’s first female doctor and founder of the Victorian Medical Women’s Society in 1895.

The following year, with support from 10 other women doctors, Dr Stone raised funds to open the Victoria Hospital for Women and Children.

Professor Simonis wrote: “I took to exploring medical women’s history because I have realised that, in my training, there were not many female role models to whom I could aspire.

“When I discovered they did exist and, indeed, had existed for more than a hundred years, I wondered why that story had not yet been told.”

Asked by AusDoc what advice she would give the new generation of doctors, she says: “Just do what you love doing.

“And if you feel stuck, ask yourself why you feel that way. When you face that question throughout your career, you open doors to other opportunities and that’s usually by offering to help others.”

She adds: “It feels great being of service, moving into uncharted areas and learning new things along the way. No education is ever wasted.”

Professor Simonis was awarded an AM today for her significant service to medicine and to women’s health.

Dr Kerry Breen AO, Melbourne, Victoria

When Dr Kerry Breen considers his long (and distinguished) career he comes to the conclusion that his most important contribution to the greater good was setting up the Victorian Doctors Health Service.

It was the early 1980s.

The doctors it would care for were not much talked about because they were impaired — addictions and mental health problems in the main.

And in some cases their practice had come to the attention of the Victorian Board of the Medical Board of Australia of which Dr Breen was president.

Their existence for the wider profession verged on the taboo.

“You don’t mull over all the things you’ve done in your life,” Dr Breen says.

“But yes, when asked to name the thing that I’ve been happiest about, particularly in terms of medical regulation, it was getting that health program up and running.

“From the beginning it has done a wonderful job in getting unwell doctors back.

“It depends on the illness of course, but with addiction to narcotics, around 80% of those they help will be off drugs and back in the workforce.

“It has worked to change people’s lives for the better.”

This is of relevance because it explains why Dr Breen is one of AHPRA’s most vocal critics.

He believes the operations of the AHPRA monolith since its emergence have been crippling the people he says are in need of help.

“The project team that set up AHPRA a decade ago told the medical profession it was going to pick up the best of the existing medical board systems. They did not.

“They refused to fund our doctor’s health program for about three years.

“The other thing is that when I was on the medical board, our complaints handling was done by two experienced doctors, people with a background in medical administration and general practice.

“They were the first people to look at a complaint and then they would interview the complainant and, if necessary, the doctor.

“Then they’d come to a board meeting and they’d bring their written report and the board members would discuss the options.

“But the current model of AHPRA is not like that. The people who handle the complaints have limited medical knowledge or medical experience, and it’s all done by letters and email.

“The process, as we know, is inhumane. People are damaged by it.”

As a gastroenterologist in Melbourne, he says his career in medical regulation was an accident.

“It was strange. It was 1981. Most doctors had forgotten that the medical board in Victoria existed.

“Out of the blue, I got a letter from the state health minister telling me I’d been appointed to the board. I hadn’t applied, nothing, I was just appointed.

He says he was not worried about the idea of casting judgement on his peers.

But he says that was partly because he was naïve and, initially at least, he knew so little about what he was meant to be doing.

Some of the early cases were serious. He remembers dealing with an orthopaedic surgeon who had been sexually abusing women.

“It was just terrible. That really shocked me.”

At the other end it was doctors receiving complaints for being lazy with the paperwork when asked for things like medical reports.

“They needed a kick up the backside.”

The regulation of doctors and the arts it demands has generated a booming global academic industry in recent years.

Its main focus has been attempts to identify red flags for doctors who will eventually put their patients in harm’s way.

In terms of early warning systems, it seems the most powerful (and reliable) predictor identified so far is the number of complaints the doctor has received before — which does not seem to be that revelatory.

Dr Breen says through his dealings with doctors whose standards of care have sunk, nothing is obvious.

As a result of this he is not a big fan of the Medical Board of Australia plan for the mandatory health assessments for all doctors aged 70 and over.

What is happening in terms of the project announced back in 2017 has become a mystery of sorts.

The board is strangely quiet on the progress it has made since then.

But Dr Breen, who has now retired from practice himself, says this: “In Canada, two provinces experimented with it 20 years ago. Every doctor over 70 would be subjected to a practice audit.

“What happened? Almost all of the doctors who got the letter saying ‘You’re about to be audited’ chose to retire. They found it threatening. And I’m sure that led to [the] loss of quite a lot of doctors.

“Yes, they may have picked up a few incompetent doctors, but they lost a lot of competent ones.

“Anyone who is working on this for the Australian system has to move very, very carefully.”

In terms of AHPRA he is out in the public domain demanding not tweaks but its dismantling.

“I think AHPRA is the worst. If you’re going to design an effective system for medical regulation, you wouldn’t design it like AHPRA is.

“It only covers half the country, there’s no single health minister involved, it’s remote from the professions and it’s a disaster.”

Dr Breen was awarded an AO in the King’s Birthday Honours today.

| All the GPs honoured today |

| Officer of the Order of Australia (AO) Professor Jane Gunn, Melbourne Professor Michael Kidd, Sydney Member of the Order of Australia (AM) Associate Professor Rosanna Capolingua, Perth Dr Caroline Elliott, Adelaide Associate Professor Gary Kilov, Launceston, Tasmania Professor Danielle Mazza, Melbourne Dr Elizabeth Rickman, Sydney Clinical Associate Professor Magdalena Simonis, Melbourne Professor Simon Willcock, Sydney Commodore Nicole Curtis, Canberra Medal of the Order of Australia (OAM) Dr Margaret Beavis, Melbourne Dr Ian Cameron, Newcastle, NSW Dr Paul Collett, Gloucester, NSW Dr Diana Coote, Warialda, NSW Dr Andrew Davies, Perth Dr Mary Dunne, Woorabinda, QLD Dr Clement Gordon, Warialda, NSW Dr Clive Hume, Adelaide Dr Stephen Jamieson, Canberra Dr Philomena Joshua Tenni, Melbourne Dr Susan Lester, Geelong, VIC Dr Frank Meumann, Claremont, Tasmania Dr Michael Monsour, Maryborough, QLD Dr Stephen Morris, Parkes, NSW Dr Gerard Quigley, Cummins, SA Dr Norman Roth, Melbourne Dr Michael Simpson, Montville, QLD Dr Keith Skilbeck, Melbourne Dr Dennis Sundin, Sydney Notable non-GP specialists Companion of the Order of Australia (AC) Emeritus Professor Caroline Bower, Perth (public health physician) Professor David Hunter, UK (epidemiologist) Officer of the Order of Australia (AO) Clinical Associate Professor Robert Ali, Adelaide (addiction medicine specialist) Dr Kerry Breen, Melbourne (gastroenterologist) Professor David Ellwood, Gold Cost, QLD (obstetrician/gynaecologist) Professor Michael Horowitz, Adelaide (endocrinologist) Clinical Professor Brendon Kearney, Adelaide (public health physician Professor Glen Liddel-Mola, Papua New Guinea (obstetrician/gynaecologist) Professor Grant McArthur, Melbourne (medical oncologist) Clinical Professor Ruth Marshall, Adelaide (rehabilitation specialist) Dr Sandra Staffieri, Melbourne (paediatric ophthalmologist) Professor Donald Wilson, Sydney (public health physician) Professor Erica Wood, Melbourne (haematologist) Professor John Zalcberg, Melbourne (medical oncologist) |

AusDoc always scours the Australia Day and King’s Birthday Honours lists to recognise all the GPs, but sometimes names slip our radar.

If you know somebody we missed this time, please email antony.scholefield@adg.com.au.

Read more: