Sexist textbooks, BERT’s return and the $500K defamation case: AusDoc stories of 2019

It’s part two – the fate of BERT; one of the biggest defamation payouts in Australian legal history; and, to begin with, why Advanced Examination Techniques in Orthopaedics is no longer on the med school reading list.

Number 12: The ‘hilariously wrong’ medical textbook

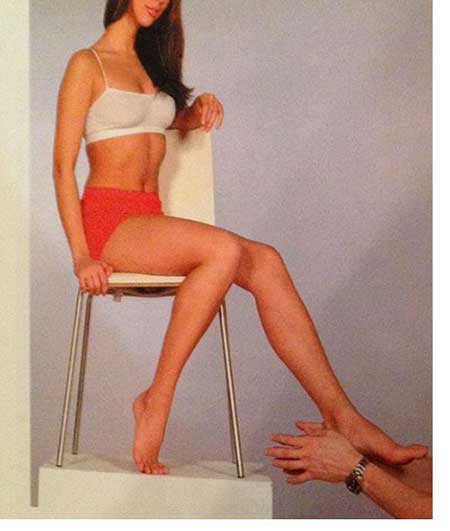

It was a page-turner for all the wrong reasons: the orthopaedic textbook illustrating for its medical audience how best to conduct an advanced foot examination.

For some reason, the patient subject to this assessment was dressed in a see-through bra and red underwear.

The publishing wardrobe budget must have been tight, since another woman wore the same bra while undergoing a brachial plexus exam, although the men involved did manage to secure themselves a shirt, tie and pair of trousers.

But Advanced Examination Techniques in Orthopaedics, a common reading requirement of many medical schools around the world, was destined for the big paper shredder in the sky when this year Sydney neurologist Dr Kate Ahmad tweeted pictures from it, drawing thousands of shares and comments.

“If you don’t think women in medicine have problems — check out the required textbook for orthopaedics at one Australian med school,” Dr Ahmad said.

The offending book, dubbed “almost soft-core porn”, was first published in 2002.

Cambridge University Press, its publisher, responded to the uproar, admitting some pictures were “inappropriate” but stressing that its 2014 edition was much better.

But when the 2014 edition subsequently surfaced on social media a few hours later, it was also dubbed “hilariously wrong” for depicting another young woman being examined while wearing a push-up bra.

Dr Ahmad said the problem was the books were still widely available and used, and it fuelled the myth that made orthopaedics an unattractive specialty for female surgeons.

“They promote a ‘boys club’ culture, where male surgeons bond over the ogling of attractive women, even when this is most inappropriate, as in the case of the vulnerable patient.”

Cambridge University Press responded for a final time: “We deeply regret this happened and are removing the current edition from sale.

“It will remain out of print until a thoroughly revised third edition is produced.”

Number 11: The return of BERT

Many of you may recall when a mass letter-writing campaign organised by the Department of Health sent GPs damn near postal.

Some 5000 GPs received letters saying they were in the top 20% of opioid prescribers in Australia, a point reinforced with graphs comparing them to their peers.

The letters raised the spectre of referral to the Medicare watchdog, the Professional Services Review, for overservicing.

In July, there was a sort of mea culpa.

Chief Medical Officer Professor Brendan Murphy admitted there had been flaws in this approach because among those doctors targeted were those working in aged care, palliative care and cancer care.

“We are aware that these initial letters did cause some anxiety and distress for some GPs, and I apologise for that,” he said.

The letter campaign was devised by the Department of Health’s ‘nudge unit’ — the Behavioural Economics and Research Team, or BERT.

Its remit is to “incorporate behavioural sciences into government interventions to improve policy and program outcomes”.

In the attempt to nudge doctors to reduce inappropriate opioid prescribing, peer comparisons were included in the letters, and the CMO’s signature was at the bottom.

But, despite the apologies, the letters kept coming. Over the course of 2019, they targeted high claimers of MBS items for skin cancer excisions, imaging and acupuncture.

The AMA said it had worked with the Department of Health to ensure the newer letters were less threatening and more educational.

However, the RACGP warned of the dangers.

“There is a growing perception that compliance activities are designed to monitor and target statistical outliers, as opposed to targeting fraudulent activity,” it said.

“This negative perception of existing compliance processes and the resulting stress associated with these processes … can interfere with good patient management and the delivery of appropriate and quality care.”

We still await the publication of what the mass letter drops have achieved in terms of improving clinical care and reducing Medicare misclaiming.

But it seems BERT’s employment at the federal Department of Health has become permanent.

Number 10: ‘Piss off. I don’t have any money to give you greedy people.’

A Sydney plastic surgeon walked out of the NSW Supreme Court in June with a claim to $530,000 in compensation over two defamatory Google reviews.

Dr Kourosh Tavakoli’s website described him as the Australian pioneer of the “Brazilian butt lift” and the “Chanel of plastic surgery”.

But, according to court findings, traffic to his website dropped 24% after a disgruntled patient falsely accused him of incompetence and charging her for a buccal fat extraction he never performed.

A judge issued an injunction banning Cynthia Imisides from repeating the claims. But, she did anyway, leading Dr Tavakoli’s lawyers to warn her she was in contempt of court.

Ms Imisides responded with one emailed paragraph: “Piss off. I don’t have any money to give you greedy people.”

She never appeared in court to defend herself.

Dr Tavakoli was granted an order for more than half a million dollars in compensation; however, it’s not clear whether he has received any payment.

This figure eclipsed the $480,000 awarded to orthopaedic surgeon Dr Munjed Al Muderis two years ago over a social media hate campaign involving threats to kill, which was, at the time, declared to be the first defamation payout to a doctor over claims made by a patient.

Dr Al Muderis has yet to received a cent either from his abuser.

But Dr Tavakoli’s case has raised questions about Google reviews — the effect they can have on a doctor’s reputation and the difficult process of persuading the internet behemoth to delete them.

The company claims it has spam-detection software that can detect fake reviews.

However, AMA NSW has been lobbying the tech company to allow medical practices to disable the reviews function completely, partly because doctors were limited in the way they could respond due to AHPRA’s rules on testimonials.

Google said no.

Undeterred, AMA NSW president Dr Kean-Seng Lim, a GP, said he was up for the David/Goliath fight.

“We are not dropping this matter.”